The U.S. government is enacting measures to save the airlines, Boeing, and similarly affected corporations. While we clearly insist that these companies must be saved, there may be ethical, economic, and structural problems associated with the details of the execution. As a matter of fact, if you study the history of bailouts, there will be.

The bailouts of 2008–9 saved the banks (but mostly the bankers), thanks to the execution by then-treasury secretary Timothy Geithner who fought for bank executives against both Congress and some other members of the Obama administration. Bankers who lost more money than ever earned in the history of banking, received the largest bonus pool in the history of banking less than two years later, in 2010. And, suspiciously, only a few years later, Geithner received a highly paid position in the finance industry.

That was a blatant case of corporate socialism and a reward to an industry whose managers are stopped out by the taxpayer. The asymmetry (moral hazard) and what we call optionality for the bankers can be expressed as follows: heads and the bankers win, tails and the taxpayer loses. Furthermore, this does not count the policy of quantitative easing that went to inflate asset values and increased inequality by benefiting the super rich. Remember that bailouts come with printed money, which effectively deflate the wages of the middle class in relation to asset values such as ultra-luxury apartments in New York City.

If It’s Bailed Out, It’s a Utility

First, we must not conflate airlines as a physical company with the financial structure involved. Nor should we conflate the fate of the employees of the airlines with the unemployment of our fellow citizens, which can be directly compensated rather than indirectly via leftovers of corporate subsidies. We should learn from the Geithner episode that bailing out individuals based on their needs is not the same as bailing out corporations based on our need for them.

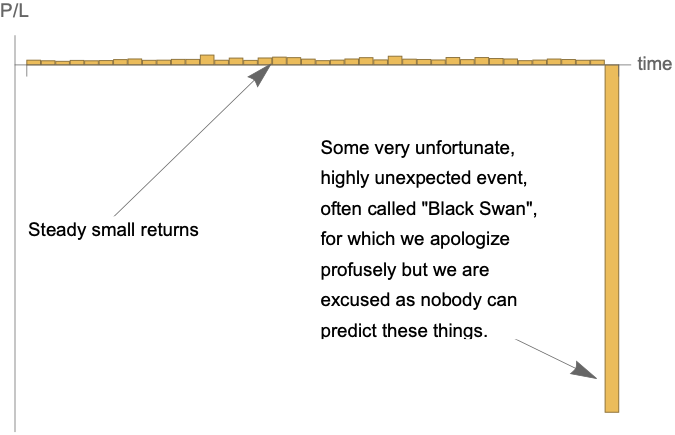

Saving an airline, therefore, should not equate to subsidizing their shareholders and highly compensated managers and promote additional moral hazard in society. For the very fact that we are saving airlines indicates their role as utility. And if as such they are necessary for society, then why do their managers have optionality? Are civil servants on a bonus scheme? The same argument must also be made, by extension, against indirectly bailing out the pools of capital, like hedge funds and endless investment strategies, that are so exposed to these assets; they have no honest risk mitigation strategy, other than a trained naïve reliance on bailouts or what’s called in the industry the “government put”.

Second, these corporations are lobbying for bailouts, which they will eventually get thanks to the pressure they can exert on the government via lobby units. But how about the small corner restaurant? The independent tour guide? The personal trainer? The massage professional? The barber? The hotdog vendor living from tourists near the Met Museum? These groups cannot afford lobbyists and will be ignored.

Buffers Not Debt

Third, as we have been warning since 2006, companies need buffers to face uncertainty –not debt (an inverse buffer), but buffers. Mother nature gave us two kidneys when we only need about a portion of a single one. Why? Because of contingency. We do not need to predict specific adverse events to know that a buffer is a must. Which brings us to the buyback problem. Why should we spend taxpayer money to bailout companies who spent their cash (and often even borrowed to generate that cash) to buy their own stock (so the CEO gets optionality), instead of building a rainy day buffer? Such bailouts punish those who acted conservatively and harms them in the long run, favoring the fool and the rent-seeker.

Not a Black Swan

Furthermore, some people claim that the pandemic is a “Black Swan”, hence something unexpected so not planning for it is excusable. The book they commonly cite is The Black Swan (by one of us). Had they read that book, they would have known that such a global pandemic is explicitly presented there as a white swan: something that would eventually take place with great certainty. Such acute pandemic is unavoidable, the result of the structure of the modern world; and its economic consequences would be compounded because of the increased connectivity and overoptimization. As a matter of fact, the government of Singapore, whom we advised in the past, was prepared for such an eventuality with a precise plan since as early as 2010.

Written By

with Mark Spitznagel

Republished from Incerto.