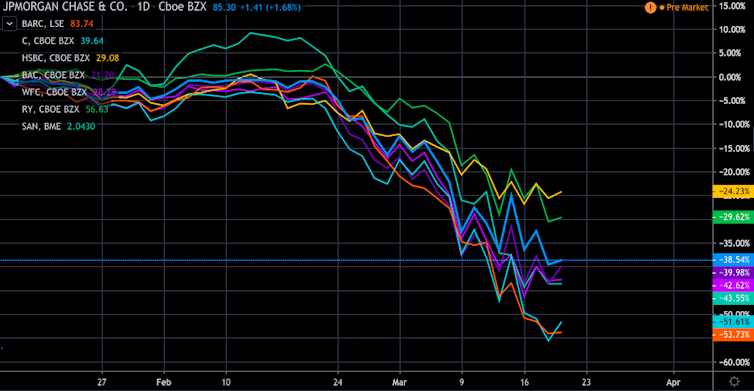

One of the most visible outcomes of the COVID-19 crisis is the mayhem in the global stock markets. Between February 20 and March 19, the S&P 500 index plunged from 3,373 to 2,409, the FTSE 250 from 21,866 to 12,830, and the Nikkei from 23,479 to 16,552. The oil price war, in which Russia and Saudi Arabia have been driving down the price of the commodity by ramping up production, has arguably played a role in this rout. But the more recent plunge is much more likely to be on account of the uncertainty about the overall impact of the pandemic.

As people adjust to life in this crisis, investors are increasingly shifting focus to banks and what events imply for the stability of the sector. In the stock market, investors have taken a view of banks that is not too different from their overall view of the economy.

Over the same time period as above, for example, Citigroup’s share price fell from US$78.22 to US$39.64 (£66.27 to £33.58), JP Morgan Chase from US$137.49 to US$85.30, and Barclays from £181.32 to £86.45. There has also been a recent increase in the credit default swap spreads of banks, which is a measure of their creditworthiness. This has renewed fears about another banking crisis.

Bank stocks go down

To be fair, the mayhem in the stock market is unlikely to push many banks into difficulties, since the assets they hold are not mainly made up of investments. For example, the HSBC UK annual report 2018 indicates that, at the end of that year, loans and advances to customers accounted for £174.8 billion of the total £238.9 billion in assets – a 73% proportion.

This means that HSBC has much more to lose from borrowers defaulting on these loans and advances – and potentially never paying them back – than from its investments into the likes of shares and bonds falling in value. They make up a much smaller proportion of its holdings, and this is likely to be true of most banks.

But as COVID-19 shuts down large segments of the economy – not just because of factors such as supply chain disruption but simply because of the effects of social-distancing restrictions – the risk of mass loan defaults continues to mount. Companies experiencing severe drops in revenue may struggle to repay loans. Households may struggle to pay off credit cards and make mortgage payments. The question is whether banks will be able to withstand the pressure from this in months to come.

Fit for purpose?

Some of the things that have previously exacerbated banking crises are, at least for the moment, less of a threat this time. Central banks have been much quicker than in 2007-09 to signal that they stand ready to provide unlimited liquidity to the market – having learned their lesson last time.

The Federal Reserve Bank in the US, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank (ECB) have all been lowering interest rates and/or announcing large-scale purchases of government bonds and other assets in a new round of quantitative easing. This makes it much less likely that the money markets will freeze up like they did in the global financial crisis. In the early days of that crisis, that was what had threatened the liquidity and hence the stability of the banking sector.

The cut in interest rates may, of course, adversely affect the net interest margins of banks – the difference between the interest rate they pay (principally) for deposits and the interest rate they earn on loans and other interest-bearing assets – but that may not threaten their viability in the short run.

At the same time, the UK banks are well capitalised, meaning they have large enough capital reserves to cope with lots of loans failing, according to the Bank of England’s December statistical release.

The three key measures of bank capital – the overall capital ratio, Tier 1 capital ratio and Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratio – were 21.0, 17.6 and 15.3 respectively in the third quarter of 2019. These ratios were up to three times higher than at the start of the global financial crisis, according to the Bank of England’s Financial Stability Report from December 2019.

The report also noted that the annual stress tests carried out on the UK banks show they would be “resilient to deep simultaneous recessions in the UK and global economies” that are worse overall than last time around, along with a large fall in asset prices.

The Federal Reserve and ECB reached similarly positive conclusions about the US and eurozone banks in 2018 and 2019. Going by these numbers and reports, the banking sectors in Europe and the US are more resilient today than at the beginning of the 2007-09 crisis.

Notes of caution

In normal circumstances, banks reduce their risks of being hit by swathes of loan defaults by diversifying their lending across different industries and regions. This may not help in a pandemic, if many industries, sectors and countries go into a deep recession simultaneously.

Also, any recession may be deeper than expected if the major economies end up incapacitated for an extended period of time, say a year or more, as opposed to the more optimistic time frames of several months that political leaders have sometimes referred to.

Going into the future, this means that a lot will depend on the duration of the crisis, and how much support is provided by governments and central banks to companies and households.

Early signs indicate that governments will spend heavily, though this will doubtless vary across countries. The UK has already announced several packages worth many billions of pounds, and is still unveiling more support for affected businesses and households.

One big unknown is whether there will be another surge in infections and deaths after the first one has been arrested. If so, the crisis would last longer and put much more pressure on the banking sector.

In sum, for the banks in the US and Europe, there could well be tough times ahead, though they are at least arguably in a better position to withstand the headwinds than they were before the global financial crisis.

![]()

Sumon Bhaumik, Chair in Finance, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.